The Sorrow Songs - Notes & Lyrics

UNKNOWN AFRICAN BOY (D.1830)

This was the very first of The Sorrow Songs. It came to me as I paced up and down my local beach, wrestling with the tragic story I had just read. Many slave ships passed by the Isles of Scilly during the era of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (1526 - 1867 approx). The tricky waters in this area meant that many ships were wrecked. In the case of this ship, the exhausted captain mistook the day mark of St Martin’s for the lighthouse of St Agnes, and the ship was wrecked. A local newspaper article of the time lists some of the items washed up on shore. The list includes palm oil, several hundred elephant tusks, a box of silver dollars, two boxes of gold dust, and the body of an unknown ‘West African boy’, estimated age around 8. The boy is buried in St Martin’s churchyard, Isles of Scilly. This song is from the perspective of his mother.

O my brown arms, they are sad and empty,

O where, o where is my little son?

He’s stolen away by English slavers,

With a cudgel blow, and a pointed gun.

My riven heart, it is wide with sorrow,

O where, o where is my darling boy?

Thrust into a sack with babes and younglings,

By slavers in the King’s employ.

Lully, my dear babe, where’er you be,

May the arms of the ocean be cradle for thee.

Ripped o so cruel from his loving mother,

My darling babe, to be bought and sold.

His skin rubbed raw by iron shackles,

He gulps foul air in the ship’s dank hold.

O I’ll send my spirit out into the darkness,

Into stars, and the wind, and the sea I’ll go;

My spirit will fly into earth and water,

That a mother’s love he might then know.

Lully my dear babe, where’er you be,

May the arms of the ocean be cradle for thee.

If the sea be your bed, and the waves be your pillow,

May the sun in the sky keep you from all harm.

The earth is your mother now, dear baby;

She will hold you safe in her soft, brown arms.

Lully, my dear babe, where’er you be,

May the arms of the ocean be cradle for thee.

O earth, cradle my son for me

(Lully, lullah, lully, lullah)…

BLACK JOHN

John Ystumllyn (1730s - 1786), also known as Jac Ddu, Black Jack, or Black John, an 18th century gardener, was recently honoured as the UK’s first known Black horticulturalist, with a yellow rose named after him. His real name is not known, but he was abducted as a child and trafficked into slavery. He came into the ownership of the Wynn family of the Ystumllyn estate, Gwynedd, North Wales. Arriving in Wales as a traumatised child, he quickly became fluent in Welsh and English, and showed a natural skill for gardening. He became a very respected gardener, and married a local Welsh girl, Margaret Gruffydd. They had seven children and some of their descendants are said to live in the area… Jac was known for his quiet temperament, his gentleness, and his love of playing the violin.

CHORUS:

Black John makes the garden grow, bloom and blossom flourish.

In this land a seed did sow, that never now can perish.

Once I was a happy child at play, it’s sometimes hard to remember…

Then bright sunlight to the darkest depths gave way. That memory makes me shudder.

I cannot help but call to mind the torments that befell me.

But as a grown man, now I find I am proud Welsh man Jac Ddu.

My love is for the earth and all that grows, I work the land for hours.

Come rain, or mist, or when the wild wind blows, I tend the plants and flowers.

Sometimes when I have finished work, the master’s gardens call me.

I’d rather be with soil and bark, all in sweet nature’s company.

I am a man who likes a peaceful life, and music on my fiddle.

When shadow’s fall, I dream my own dear wife - sweet smile and tidy middle.

Sometimes the maidens in this town, for my dark face mislike me.

But Margaret’s fairest of them all, she’ll wed proud Welsh man Jac Ddu.

THE BEAUTIFUL SPOTTED BLACK BOY

George Alexander Gratton (1808-1813) was an African child who had vitiligo, a skin condition where pigmentation is absent in areas of the skin. During the 18th and 19th centuries, it was fashionable to exhibit Black or dark-skinned children with vitiligo, billing them as ‘spotted children’. People would flock to see them, often paying large sums of money for the experience. John Richardson was a successful English showman and circus entrepeneur, who paid 1,000 guineas for George and exhibited his purchase in his ‘travelling freak show’. Richardson is said to have treated George Alexander as a son, and to have been extremely fond of him. This of course does not sit easily with the fact that he was also the boy’s legal owner, and he exhibited him… Nevertheless, when little George died at a very young age (estimated age 4-8) of a “gathering of the jaw” (likely an infection or tumour), Richardson was distraught with grief. He was also said to have expressed concern that someone might steal the body. George’s burial was delayed for three months, as Richardson commissioned a brick vault in the churchyard of All Saints, Marlow. He willed that this would also be his own final resting place, with his headstone joined to the boy’s. This song is a conversation, or an exchange of viewpoints, between George and his ‘owner’.

Roll up and see my beautiful spotted black boy!

He’s a charming creature,

Dappled and speckled and spotted all o’er,

See nature never made one finer!

Gentlemen, ladies, friends - roll up!

He’s just like a sweet Dalmatian pup.

And for a small fee, you can see his pied face,

His beautiful spotted carapace.

On St. Vincent’s Isle, in the West Indies,

Mother Nature’s known for her wild caprice.

But was magic afoot on that fateful night,

When this child was born both black and white?

On St. Vincent’s Isle, ‘neath the sun’s bright glare,

You took out your purse, bought me fair and square,

And then put me on show in every town,

All for your wealth and your renown…

Ah, but Sir, I wish that you had not bought me

With your thousand guineas,

Put me in cages and drag me about

The length and breadth of all the nation.

Gentlemen, ladies, children stare,

They gawp at my face, they touch my hair.

They poke me and prod me and watch me at play,

O! How I wish they would go away.

I fear they’d never understand,

I fear they’d think me strange or wild;

I could not care more for this infant so pure,

If he were my own, my own dear child…

I scarcely understand myself,

It steals like a thief across my breast.

Deprived of my father and mother’s own love,

I think I may love him best…

MAD-HAIRED MOLL O’BEDLAM

The image that inspired this song has been very elusive… At this point I am still unable to find it. A few years ago I was researching the concept of ‘mad hair’ in Western culture. I was interested in the way that very curly or very thick hair is often read as a signifier for wildness, or even insanity. Caricatures of a ‘mad professor’ or ‘mad genius’ usually include wild, frizzy or curly or textured hair, standing proud of the head. Early photographs of women from Victorian asylums often show disarrayed hair as a sign of a disordered mind. Think of the Victorian literary conceit of the madwoman in the attic (Mr Rochester’s first wife in Jane Eyre is a perfect example of this, with her wild, Caribbean hair). I was interested in the ways that natural, textured African hair can be read similarly, and how this widespread notion of ‘mad hair’ can be harmful to people whose hair naturally grows this way. Whilst scrolling through some 19th century photographic portraits of women inmates in an English psychiatric hospital, I stopped in my tracks when I saw that one of the pictures was of a light-skinned Black woman of my sort of skin tone. There was some information about her. She was aged 19. She had spoken ‘the wrong way’ to an officer of the law. She died in incarceration. I couldn’t get her, or her story, out of my mind… I imagined a whole narrative for her, including the circumstances around her arrest. I imagined that prior to this, she was known for her beautiful hair. It became a feminist song, as well as an anti-racist one. I still haven’t managed to find the picture, so until I do, you’ll have to take my word for it…

I am Moll Brown of London Town,

And I’m twenty years and two, boys.

I am as Black as Black might be,

And I’m London through and through, boys.

When I was born one winter’s morn,

The bells of Bow did sound, boys.

Bu for checking of a policeman I

In Bedlam now lie bound, jolly boys.

O in Bedlam I do lie bound.

O, I’m Moll with me mad, mad hair.

O, they say I’se mad as a mad March hare.

I was renowned for miles around

For my thick raven locks and my beauty.

Until my life was crushed in the fist

Of a Peeler that’s new on duty.

I’d tie my hair with greatest care,

In rolls and in tucks and in coils, boys.

With ivory combs and with glass beads adorned,

And perfumed with such fragrant oils, jolly boys.

And perfumed with such fragrant oils.

That day I walked so high and proud,

In the morn when the streets are empty.

‘Black wench!’ Says a voice, ‘it’s you I’ll have!

And I’ll warn ye not to tempt me’.

He grabbed me by my middle so small,

Shoved me into a doorway.

O I kicked, and I bit, and I hollered full sore,

But I could not get away, jolly boys.

No, I could no get away.

That Policeman, he was angered so cruel,

For I’d scratched at his face till it bled some.

He says I’se mad, and dangerous too,

And he marches me straight to Bedlam.

Now I have heard it said and sung,

That Bedlam boys they are bonny.

But my world is as small as this cold cell wall,

And the straps they have tied all upon me, jolly boys,

And the straps they have tied upon me.

THE HAND OF FANNY JOHNSON

Frances Elizabeth Johnson (baptised 2 April 1778) has a memorial stone in the garden of Lancaster Priory. Her story is an unusually macabre one, if it is true… In 1996, a descendant of the Satterthwaite family decided to inter a mummified human hand that had been in he family for over 200 years. It is believed (though not known for certain) that this hand belonged to the family’s Black servant, Frances Elizabeth Johnson, or Fanny. This song is from the perspective of the hand of the departed woman, in which a tiny part of her soul essence has remained to watch over the family she served so devotedly all her life…

CHORUS:

When you bury my body down, down in the cold, cold ground,

Won’t you bury me, bury me entire and whole?

If only I could,

I’d fold the mistress’ linen,

And keep watch over the children,

And make for the master his favourite mutton

So he’ll be nourished and strong.

Ah, but death comes for us all.

Death comes for the rich and the lowly,

His fingertips prising the soul from the body,

And when it’s my time, all I ask is you’ll bury me

All entire and whole.

CHORUS.

O the family kept my hand.

Framed and embalmed o’er the fire in the parlour,

A hand keeping watch with no power to look after,

A token to lessen the pain of departure

When my life it is o’er…

Ah, but when I was a girl,

My dear mother said that a funeral is holy,

The sanctified earth receiving the body,

And in the hereafter that’s when we will all be

Remade, entire and whole.

CHORUS.

CINNAMON WATER

Mary Jane Seacole (1805 - 1881) was a Jamaican adventurer and ‘doctress’, or practitioner of folk medicine, best known for her work as nurse in the Crimean War. She set up what was known as The British Hotel, a place where wounded soldiers could rest, receive treatment, and be nourished and looked after. Mary Seacole’s knowledge of folk medicinal practices included things like hygiene and the cleaning of wounds, which was not generally practiced at the time. Happily, there is now much written about Mary Seacole, and it is quite easy to find out about her amazing life. She was an independent woman and a lover of travel and adventure, as well as a devotee of the art of nursing. Some of her remedies, including things like soursop and calabash that grow in Jamaica, form the chorus of this song.

CHORUS:

Cinnamon water, a poultice of ash,

A handful of guinea hen weed, all in a calabash.

Cinnamon water and soursop heart,

Herbs both bitter and sweet.

From the hands of the mother and daughter,

Through the mists of the past revealing,

The herbs and the cinnamon water

Hold all the mysteries of healing.

I’d practice my healing on creatures,

A tiny girl apprentice.

I’d seek out the ball-moss and sorrel,

As I learned the old ways of the doctress.

CHORUS.

So many lives lost in the Crimean War,

As battle cries resounded,

So with courage and wisdom and herbs in great store,

I set off to tend to the wounded,

I did nurse the sick and the wounded.

I’d bind up one poor soldier’s shattered leg,

And close the eyes of another,

I’d cradle a poor young man’s bloodied head,

As he did cry out for his mother.

Of glorious fame the healer’s path

Is oftentimes bereft,

So seek not for praise, nor for high renown,

Seek only to give of your gift.

HIDE YOURSELF

This song is about the Liverpool Race Riots of 1919. During this year, riots erupted in seaport cities throughout the UK. The First World War (1914-18) had left extreme levels of poverty and hardship in its wake, and many people were struggling to survive. Employers knew they could get away with paying Black and Brown people a lot less, so employers in seaport towns favoured them for jobs. This led to angry mobs of White people, who also needed those jobs, rioting and attacking the homes of people of colour. Charles Wotten (sometimes spelled Wotton or Wootton), born in Bermuda in 1895 and mentioned in the song, was murdered exactly as described. Liverpool historian Dr Ray Costello told the story of Grace Wilkie, also of Liverpool, who was aged 3 at the time of the riots. She remembers her mother putting her in the tin bath at home to keep her safe as mobs attacked the house. They pulled doors off cupboards to place over the top of the tin bath and protect the child from the missiles and broken glass. Most Black people hid in their houses during the 4 - 7 days of rioting.

Hide yourself, daughter dear,

Can you find your way round in the dark?

They think that we’ve taken their houses,

And they think that we’ve taken their work.

Bar the door, my husband dear,

Can you barricade us inside?

There’s mobs coming after us brown-skinned folk,

And I hear one poor young lad has died.

Bricks and bottles and stones,

Breaking windows and bones.

When will all this shouting die down?

They chased young Charles Wotton to the Mersey’s edge,

Throwing stones at the lad till he drowned.

O this cruel world war has left all of us poor,

And there’s never a word can console.

Now they’re ready to kill all us brown-skinned folk,

For something they think that we stole.

Come place the young babe inside this tin bath,

Can you put an old door o’er the top?

They think that we’ve taken their houses,

And they think that we’ve taken their work.

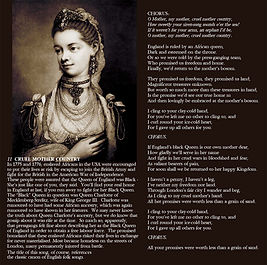

CRUEL MOTHER COUNTRY

In 1775 and 1776, enslaved Africans in the USA were encouraged to put their lives at risk by escaping to join the British Army and fight for the British in the American War of Independence. These people were assured that the Queen of England was Black - just like one of you, they said. The Queen of England is just like one of you. You’ll find your real home in England at last, if you run away to fight for her Black Queen. The “Black” Queen in question was Queen Charlotte of Mecklenberg-Strelitz, wife of King George III. Charlotte was rumoured to have had some African ancestry, which was again rumoured to have shown in her features. We may never know the truth about Queen Charlotte’s ancestry, but we do know that gossip about it was rife at the time. So much so, apparently, that pressgangs felt fine about describing her as the Black Queen of England in order to obtain a free labour force. The promised homeland that these enslaved Africans risked their lives in exchange for never materialised. Most became homeless on the streets of London, many permanently injured from battle.

The title of this song, of course, references the classic canon of English folk songs.

CHORUS:

O Mother, my mother, cruel mother country,

How sweetly your siren-song sounds o’er the sea!

If it weren’t for your arms, an orphan I’d be,

O mother, my mother, cruel mother country.

England is ruled by an African queen,

Dark and esteemed on the throne.

Or so we were told by the press-ganging team,

Who promised us freedom and home.

Finally, we’d return to the mother’s bosom.

They promised us freedom, they promised us land,

Magnificent treasures unknown.

But worth so much more than these treasures in hand,

Is the promise we’d see our true home

And then lovingly be embraced at the mother’s bosom.

I cling to your clay-cold hand,

For you’ve left me no other to cling to, and

I curl round your ice-cold heart,

For I gave up all others for you.

CHORUS.

If England’s black Queen is our own mother dear,

How gladly we’ll serve in her name

And fight in her cruel wars in bloodshed and fear,

As valiant bearers of pain,

For soon shall we be returned to her happy Kingdom.

I haven’t a penny, I haven’t a leg,

I’ve neither my freedom nor land.

Through London’s fair city I wander and beg,

As I cling to my cruel mother’s hand.

All her promises were worth less than a grain of sand.

I cling to your clay-cold hand,

For you’ve left me no other to cling to, and

I curl round your ice-cold heart,

For I gave up all others for you.

CHORUS.

All your promises were worth less than a grain of sand.

THE FLAMES THEY DO GROW HIGH

More Black history from Wales, this song is the story of twins June Allison Gibbons and Jennifer Gibbons, born 1963 (Jennifer died in 1993). The twins’ parents came to the UK from Barbados in the early 1960s as part of the Windrush generation. Their father worked for the military and they moved around a lot as children. In 1974 they settled in Haverfordwest, Wales. June and Jennifer were highly sensitive and intensely creative children, who chose only to communicate with each other in a ‘secret’ language or idioglossia. This secret language baffled experts for some time, with some ‘experts’ wondering whether the girls were speaking an ‘African click language’. Later it was found to be English, spoken very fast and with the stresses in unexpected places. As the only Black children in their primary school, June and Jennifer were bullied. The school’s intervention was to allow the twins to go home a few minutes early each day, to avoid the bullies. The twins retreated further into their private worlds and their deep bond, becoming intensely prolific writers of complex and long-running dramas, acted out by their dolls. As they hit their teen years, the stories became more and more sophisticated. The twins decided to pool their benefits money and buy a typewriter, and also paid for some of their novels to be published. They lived an intense inner life, but tragedy struck in 1981. The girls, beginning to rebel, committed some petty theft and other crimes. When they set a fire in an abandoned building they were sentenced to indefinite detention in Broadmoor under the Mental Health Act. When Jennifer died suddenly in 1993 of inflammation of the heart, June was finally released. June and Jennifer Gibbons are known as outsider writers. Copies of the twins’ self-published novels The Pugilist, The Pepsi-Cola Addict, and Discomania (which you can hear recited at the end of the song) do exist, but they are extremely rare.

CHORUS:

O the flames grow high, and the flames grow low,

Our secret tongue no soul may know,

The flames grow low and the flames grow high,

We made vast worlds in a needle’s eye.

Twin hearts, knitted together all in the dark,

Nothing can sever, no thing part,

O cleave to me! The flames they do grow high, O.

Wild universes they made in their bedroom,

Tapping at keys in the day’s gloom,

I cleave to you! The flames they do grow high, O.

Their twin tongue

Baffled the bullies in wait for them

Flummoxed the staff and the psych team,

O cleave to me! The flames they do grow high, O.

On the top stair,

Trays on their laps in the TV’s glare,

This world of dust cannot compare

To the life within! He flames they do grow high, O.

Teen hearts,

Jealousy creeps as desire sparks,

Hand in hand mischief and fires start,

O cleave to me! The flames they do grow high, O.

And then sentence was passed,

In the asylum the twins were cast,

Till death came between them and held fast,

I cleave to you! The flames they do grow high, O.

If someone had compassion shown,

Who knows what stories may have grown?

They once were two, now two are one,

And flames they do grow high, O.

The Pugilist. Discomania. The Pepsi-Cola Addict.

GO HOME

Of all The Sorrow Songs, this is the only one that is not specifically rooted in a particular time, place or individual’s story. This song is for all the people who have ever been made to feel unwelcome in the place they have chosen to call home.

Home, o’er the footbridge.

Home, through the park.

Over the fields at the edge of dark.

Tired from the factory,

I’ve laboured all week;

Wandering home for the peace I seek.

But I see it in eyes,

And I hear it in calls,

And I read it in words

In red paint on the walls

They say Go Home, Go Home!

But this is the only home I’ve ever known,

This is My Home! My Home!

And I’ve never known another.

Home, where the heart is.

Home, where there’s rest,

The fox has its hole and the bird has its nest.

My head aches from worrying,

And these shoes, how they chafe,

Just one more street-lamp then home where it’s safe.

But my stomach knots up

With familiar dread,

As the voices rise up

And ring loud in my head,

They cry Go Home! Go Home!

But this is the only home I’ve ever known,

This is My Home! My Home!

And I’ve never known another.

And I’ve never known another home.

SLAVE NO MORE (FEAT: MARTIN CARTHY)

Evaristo Muchovela (c.1830 - 1868) is buried at Wendron Churchyard, Cornwall. This in itself might seem quite unremarkable - until you realise that the grave is actually shared by two men, slave and master. Evaristo was born in Mozambique and trafficked into slavery as a child. He was purchased as a seven year old in Brazil. The man who bought him was Thomas Johns (c.1800-1861), a Cornish copper and tin miner from Porkellis. Johns had saved enough money from mining to journey to Brazil and start a new life. What little we know of their story plays itself out in the song here. Johns really did arrange for Muchovela to have somewhere to live after his death, and also arranged for him to be apprenticed to a cabinet-maker in Redruth. He had a cabinet making business and was apparently well liked in the town. Johns died in 1861, and when Evaristo Muchovela died in 1868 he was buried with his former master. The inscription on their shared headstone forms the opening and closing of this song. When I first visited the grave, I knew I had to sing this inscription. I could hear Martin Carthy’s voice reading it out, playing the role of the Vicar at the burial… so it really was a dream come true when he agreed to do it.

Here lie the master and the slave,

Side by side within one grave.

Distinction is lost, and cast is o’er;

The slave is slave no more.

CHORUS:

Slave no more, slave no more,

The slave is now a slave no more.

Stolen was I from Mozambique, a lad so small I scarce could speak

Chained in the hold so sick and weak, my spirit it did kill.

Such sights did I see, no tongue can tell, a child engulfed by the fires of hell.

And since I survived, they thought it well to sell me in Brazil.

Fresh from my torment on the sea, a Cornish miner purchased me

He fed and clothed me speedily, he treated me right well.

O hard did I toil for many a year, but my kind master I did not fear.

A kinship and loyalty sincere, within my breast did dwell.

Both strangers on this foreign shore, with tribulation great in store,

Alas it was not long before my master’s health did fail.

Twas then the choice he gave to me, stay as serving-man or leave and be free.

I chose the first, and so did we for Cornwall soon set sail.

In Wendron town in Cornwall fair, we came to live, I served him there.

I nursed him with a brother’s care, with love did him surround.

His death came soon, but even then, he left me means to work again.

We’re buried now, two equal men, together in the ground.

Here lie the master and the slave,

Side by side within one grave.

Distinction is lost, and cast is o’er;

The slave is slave no more.